Quick Links:

- Financial Issues

- 1. No funding source has been identified for Oregon’s initial financial contribution

- 2. ODOT is falling even further behind on basic maintenance and community projects

- 3. ODOT does not have a track record of accurate project estimates and on-budget delivery

- 4. Relying on toll revenues is risky

- 5. Transit operations funding has not been identified

- Mega-project Issues

- Too High and Too Low

- Equity Issues

- Climate

Financial Issues

1. No funding source has been identified for Oregon’s initial financial contribution

A new cost estimate is due shortly, and given general inflation and specifically increases in construction costs in recent years, the range is likely to be eye-popping and significantly more than the prior estimate of $3.2B to $4.8B.

The “conceptual finance plan” for the project estimates ⅓ of funding from tolls, ⅓ from Federal grants and ⅓ from the two states. Washington passed a $1B “down payment” in their last legislative session and the project will ask the Oregon Legislature to match that in the 2023 session. No source for that $1B has been publicly identified.

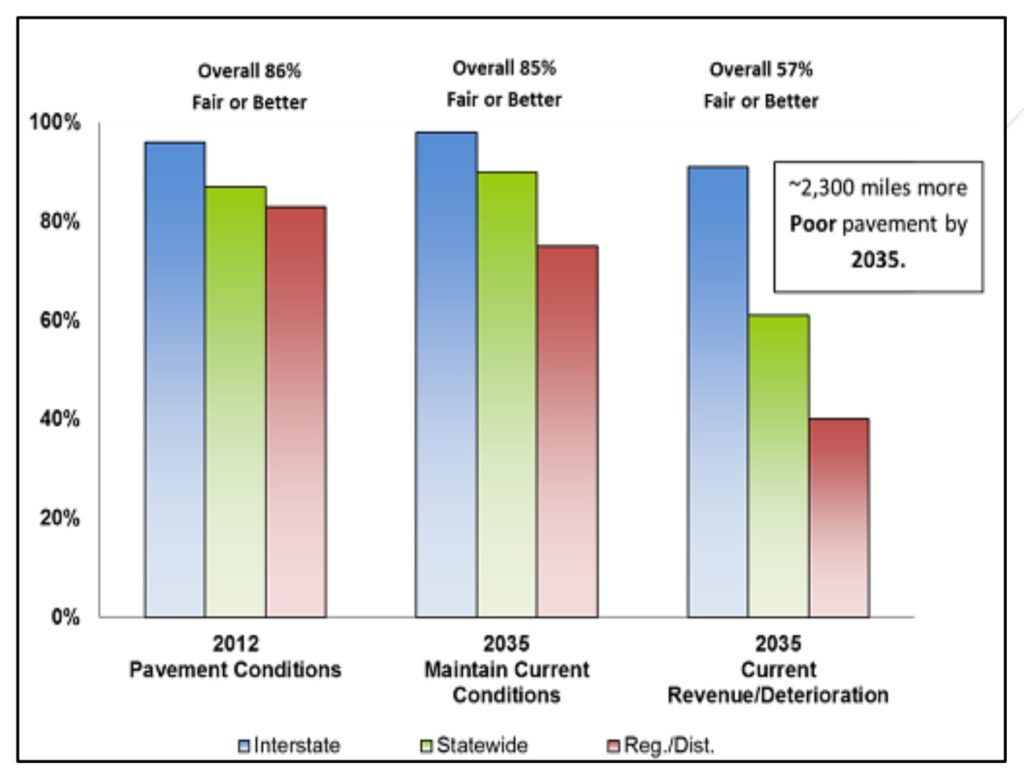

2. ODOT is falling even further behind on basic maintenance and community projects

ODOT is spending billions of dollars on new expansion projects even as the state falls further behind on the maintenance of existing roads and other pressing needs. ODOT’s federally mandated “Transportation Asset Management” report shows that Oregon is spending $320 million less per year on road maintenance than the amount needed just to keep existing roads and bridges from deteriorating further. The state has an estimated $5 billion backlog in needed seismic repairs, and large backlogs in safety, bike, pedestrian and ADA needs. ODOT routinely says it can’t pay these bills–or fund other priority projects around the state–because it doesn’t have money, even while committing to more and more expensive highway expansion projects

Read More:

3. ODOT does not have a track record of accurate project estimates and on-budget delivery

Compounding the financial risk is ODOT’s terrible track record of managing costs. Nearly every major ODOT project in the past two decades has gone 100 percent or more over its original cost estimate.

| Project | Initial Estimate | Current Estimate | Change |

| Pioneer Mountain- Eddyville Highway 20 Realignment | $110 million (2003 DEIS) | $390 million (ODOT 2012 – project incomplete) | +254% |

| Grand Avenue Viaduct Realignment | $31.2 million (Portland City Council approval, 2002) | $97.8 million (ODOT ARRA report, 2010) | +214% |

| Newberg- Dundee Bypass | $222 million (2003 DEIS) | $752 million to $880 million (2010 FEIS) | +239% to +296% |

4. Relying on toll revenues is risky

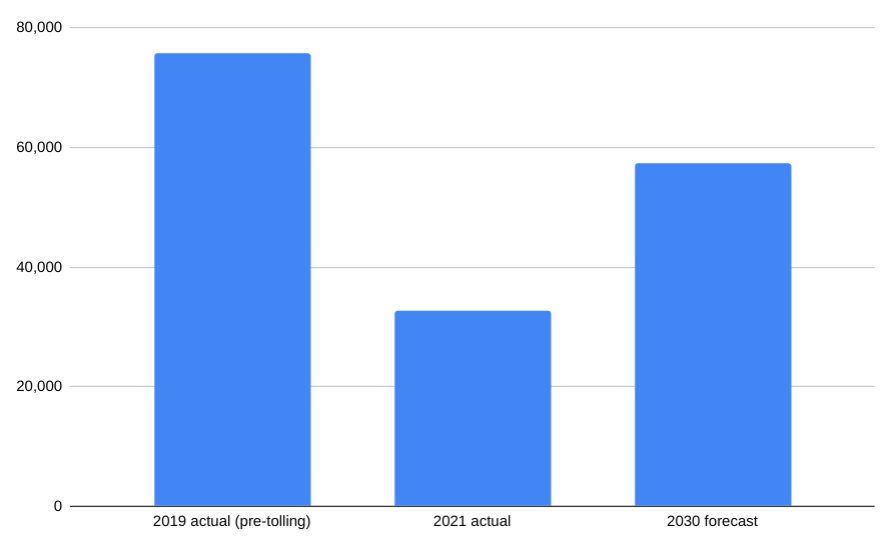

The risk of using tolls to finance a project is that charging tolls may lead to people avoiding using the facility, to the point that toll revenue is not sufficient to repay the project bonds. This is the case for the new SR99 tunnel in Seattle, now estimated to have a $200M lifetime funding gap from lower-than-estimated toll revenue.

These revenue gaps would be the responsibility of the states. The bonds are likely to be guaranteed by other transportation funding sources (like future Federal formula funds), so shortfalls could have devastating consequences on other transportation projects and needs.

This is particularly a concern for the Interstate Bridge project as to date the project has indicated that there are no plans to toll the parallel I-205 bridge.

An Investment Grade Analysis is a tool used by Wall Street to gauge the interaction of toll rates and demand. The Federal Government also requires an investment grade analysis as a condition of any federal loans. During the CRC project the Investment Grade Analysis determined tolls would need to be roughly double the rates estimated in the Final Environmental Impact Statement and that the new expanded I-5 bridge would carry fewer than 100,000 vehicles per day, about 30,000 less than the bridge carries today.. Advocates have called for an Investment Grade Analysis prior to a funding commitment by Oregon.

If we rely significantly on tolling to fund the project, then developments that are positive for climate (examples: improved transit, or demand management programs) have a negative fiscal impact on the project. We wind up rooting for more driving to pay the bonds!

5. Transit operations funding has not been identified

Both TriMet and C-TRAN in the conditions that accompanied their endorsement of the Locally Preferred Alternative made clear that their current revenue streams would not support operation of Light Rail into Vancouver. They are looking to the states to provide a new revenue source for this. Without a commitment of local revenue to fund transit operations, this project will find it difficult to qualify for federal funding.

Mega-project Issues

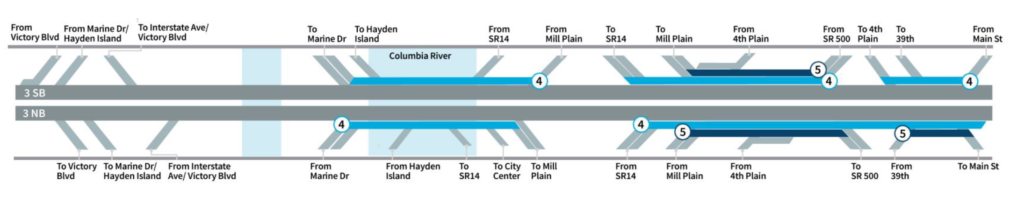

6. IBR is not primarily a bridge project, it’s a five-mile freeway project, that includes a new bridge

The project area, also sometimes known as the bridge influence area, is defined as

“extends from approximately Columbia Boulevard in the south to SR 500 in the north.”

7. No Phasing Plan

Without a phasing plan, project funders are presented with an “all or nothing” proposition to fund the project. With a phasing plan, funders can prioritize the most valuable components of the project and seek ways to pay for other components in a manner balanced with other priorities.

In 2010, an Expert Review Panel convened by governors Gregoire and Kulongoski explicitly recommended phasing for the CRC project:

“Projects of this size and scope are often planned and developed assuming a phased construction effort. Phasing (as opposed to staging) refers to the completion of some major portion of a total project, with such completion having meaningful value, yet deferring subsequent construction till later, often uncertain, dates when additional funding can be obtained.”

From a long term perspective, phasing is preferred over permanent ‘scaling back’ of the ultimate plan, particularly in growing regions such as the Portland/Vancouver Metro area.”

Read More:

Too High and Too Low

8. The current bridge design will require a steep 4% grade, based on project presentation materials

Based on project presentation materials, it appears that the bridge will have a sustained 4% grade. This steep grade for about a half mile will be a significant challenge for people walking, biking and rolling. It will reduce the potential for active transportation to be a significant mode share component for the project. To even achieve the 4% grade the project is proposing to relocate the navigation channel closer to the center of the river.

9. The Coast Guard wants a 178 foot vertical clearance

After being backed into a corner during the CRC project when the project designed for a 95 foot vertical clearance, the Coast Guard compromised and issued a 116 foot permit and required mitigation payments of $86M to upstream river users. This also triggered a year of redesign work for the project.

Following that experience, the Coast Guard renegotiated its agreement with the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to call for navigation impacts to be reviewed before starting an EIS.

In the new process the Coast Guard has recently asserted its requirement for a 178 foot vertical clearance. In spite of this, the project insists it can ultimately get a 116 foot permit from the Coast Guard. The challenge is that the final permit determination won’t come until we’ve invested more than $100M in a design and EIS process.

Equity Issues

10. Inequitable benefits and burdens

80% of the commuters on the bridge live in Clark County, WA.,The demographics of the Washington drivers going through the project area is whiter and higher income (average income is over $100k) than the Oregon neighborhoods they are driving through, resulting in a mismatch between benefits (ease of driving) and burdens (air toxics, noise, divided neighborhoods, etc.). The N and NE Portland neighborhoods have historically borne the burden of environmental racism and disproportionate pollution.

The areas of Vancouver that would be impacted from the project have some of the worst health equity disparities in the state, largely contributed to from gas and diesel emissions from cars. Expanding the freeway capacity would increase these emissions.

11. What is the opportunity cost of this project?

Even if we assume that the federal grants that help fund this project wouldn’t have otherwise gone to other projects in Oregon and Washington (which is debatable), the $1B+ that each state is going to contribute to this project could have gone to other pressing transportation, seismic, or other needs. What are we giving up by prioritizing this one very large project?

Climate

12. More Lanes = More GHGs

The project proposes at least 8 new lane miles of capacity. The project calls these auxiliary lanes but one of those lanes is as long as the entire I-405 freeway! Experience across the nation tells us that this capacity will induce more driving. One well-respected calculator puts this at 41 to 62 Million vehicle miles traveled annually.

Project supporters have sometimes suggested this is “latent demand” rather than “induced demand”. It doesn’t matter, every additional mile drive is more greenhouse gases emitted.

We know that we need to reduce the total amount of driving Americans do by 15% in order to meet the Paris Climate Accord’s 1.5C of warming target